This article was first published on I think I like it. For more in-depth reviews and discussions, visit think-like-it.com

Maxine Attard discusses process, perception, and authenticity in contemporary art-making

April 2018

Maxine Attard is a contemporary visual artist who lives and works in Malta, Europe. She began her voyage into the art world at age eighteen with her trajectory distinctly clouded by youthful uncertainty. At the time (2008) Malta's only university offered no degree in Fine Arts, and the alternative degree programmes which now exist on the islands had not yet been conceived. Attard instead studied art history and archaeology, and generally focused on discovering what felt right for her. It wasn't until she came face-to-face with Mark Rothko's Seagram series in London that she decided it was time for her to make her own art.

"My professional journey did not follow a straight line. Art has always been a part of my life, but I had plans to pursue other professions such as history or archaeology," Attard says. "I found myself constantly returning to art-making until, finally, when I was about twenty-years old, I decided to pursue an artistic career. I moved to Brighton to do an MA in Fine Arts and was privileged to be instructed by very dedicated tutors who helped me find my direction. And of course there was London – the city was just a one hour train ride from Brighton. I could visit exhibitions and attend art events. This was a real high point for me".

Attard's work builds on the transformative experience she describes having when encountering Rothko's work at the beginning of her career. "That series left a deep impression on me and I understood a few things about myself that day," she says. "I'm still not entirely sure what I am offering with my art, but I can relate to what Rothko once said to an interviewer – 'You’ve got sadness in you, I’ve got sadness in me – and my works of art are places where the two sadnesses can meet, and therefore both of us need to feel less sad'".

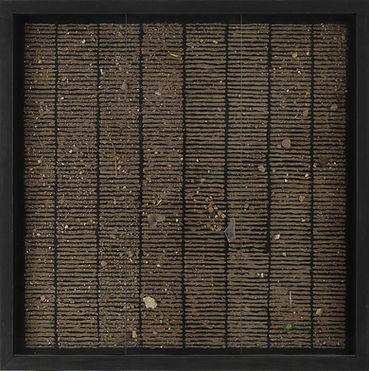

Attard's practice is heavily constructed around, and aware of, visitor perception and experience. Her works are usually large-scale, meticulously constructed geometrical compositions, made out of subtle lines and a combination of humble materials – paper, beads, cotton thread, paint, dirt, rubble. Her works are generally left untitled in an approach that she describes as 'non-suggestive'. The materials, colours, and gestures involved in Attard's art making is where the meaning is held.

"Most of the work I do with beads, for example, is untitled. Not because there is some meaning behind it which I want to hide, but because the work is what it is – it’s paper with a grid drawn on top with punched holes, and then thread and beads sewn into the paper". Attard's work has been shown in Milan, London, Brighton, and Valletta over her decade-long career, but her work is rarely influenced by the conditions of its site. The decisions she makes on scale and composition are dictated by the materials she uses. She describes her process as "waiting" for ideas to form as responses to seeing "a new material [like] a piece of plywood that has been lying around the studio". But Attard's most recent solo show demonstrated a stark departure from her un-instructive, site-less work.

In Between Obliterations, which showed at the The Mill - Art, Culture and Crafts Centre in Malta, presented a series of compositions that responded to the rapid demolition and re-constuction of the urban environment on the islands – a consequence of the country's adaptation to a quick economic upturn and a resultant swell in its real estate market. Attard uncharacteristically provided social context to this series of works, inviting reflection on change, destruction, and loss. "These works were related to a specific social/cultural issue because of the material that I was using," she explains. "The materials within the works, along with the title of the exhibition itself, each set the viewer in a specific direction".

"I consider this particular series to be something of a one-off project – a sort of branching out from my main practice," Attard says on the exhibition, "But I must admit, I have lately been contemplating my refusal to suggest any interpretational meaning to the viewer. It may be time for me to 'rethink' my process".

Attard's reflection on process came about as a direct result of this exhibition's impact, and by the thing she conventionally chooses to step back from – audience reception. By highlighting a subject that is so important to Maltese audiences at this time – the dramatic and widespread modification of the islands' urban environment – she was able to effectively calculate the communicative function of her work.

"Although I knew from the very start that the narrative element [within this series] was significant, I didn't know exactly how strong it was. In the end I realised, through the interpretations of others, that I had communicated more than I initially thought".

As Attard moves forward towards her next phase of work she will inevitably have to negotiate between her former material-led, context-free process, and one which lends itself more to narration, even didacticism. This deliberation is what makes her work so contemporary – its own functional uncertainty. Like all effective contemporary art strives to do, Attard's art challenges its own position, its role, and how it impacts and supplies meaning to viewers.

One thing Attard is sticking to is her dedication to a ritualistic process – building on a method which she describes as her personal pursuit of a perfection that cannot be attained. "I am not sure if my meticulous process is an antidote to what I view as the glitz and glam of the art world today," Attard admits. "For me my process and work is just what I do and who I am. But I do have opinions about the art world, and my reaction to it is to produce really good work. If the work is good, and by good I mean authentic, it will do its job. And by doing its job, I mean it will speak to its viewers".

As for whether she feels unsteadied by the intense influx of media and art production around her when she does pry herself away from her routine-driven art-making – not really. She does, however, question the value of it all. "I am aware how lucky I am that I live in a time when the art world is so vibrant and so important," Attard says. "But I often wonder, during visits to exhibitions and while browsing online to see what’s on – is it art I am looking at or is it just a spectacle? Is it nothing more than pure entertainment?". Seeing as some of the world's most important artists – Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, Grayson Perry, Damien Hirst, Takashi Murakami – have toyed, directly or indirectly, with this very same interrogation, it would seem beneficial to Attard to keep wondering.